Introduction to practical activities

Between the ages of 3 and 5, young human beings go through a period of rapid development of their executive functions. They want to do everything for themselves - put on their shoes, pour a drink, brush their teeth, get dressed, button their shirt, etc. And when they do it on their own, they are exercising and developing their executive functions: they retain in their memory the various stages and order them in order to achieve an objective, they control inappropriate movements and emotions and they learn to remain flexible, which is to say ready to revise their strategy in the event of errors.

Working memory. Inhibitory control. Cognitive flexibility. These three skills are of fundamental importance and are often more predictive than IQ. They enable human beings to function and to achieve the goals which they have set themselves. In addition, they are viewed as being the biological foundations of the learning process. And the good news is that in order to help children develop these cornerstone skills, which develop so rapidly between the ages of 3 and 5, all we have to do is allow them to do things on their own, remaining by their side and gradually taking more of a back seat role. Nothing more.

This was the approach that we adopted in the classroom in Gennevilliers: the whole environment (including the adults) encouraged the children to be progressively more autonomous, and this was the case throughout the day. From the moment they entered the classroom in the morning to when they left in the evening, they were encouraged to choose from a range of activities which had previously been presented to them individually and to perform those activities freely, as many times as they wanted to.

Being autonomous within a structured and structuring framework enabled the children to significantly develop their executive functions and in particular their working memory, which developed in spectacular fashion. And as we have seen, having solid executive functions makes it easier to embark on the learning process and to develop harmonious social relationships. This is what enabled the children in Gennevilliers to engage in fundamental learning with ease and to develop impressive social capacities.

First steps towards autonomy.

To begin with, we showed the young children, who were only just 2½ years old, the gestures and movements which would enable them to confidently make progress on their own in this new environment: how to unroll a mat, walk around without disturbing their classmates, sit down quietly, carry around and put away a chair, put on and take off their shoes and put them away, speak quietly, open and close a door, blow their nose, etc. We showed them these movements in a precise and ordered way so that they engrained themselves in an optimal fashion in the children's brains, as you can observe by watching the following video.

There are other videos of this kind for you to watch here.

Practical activities.

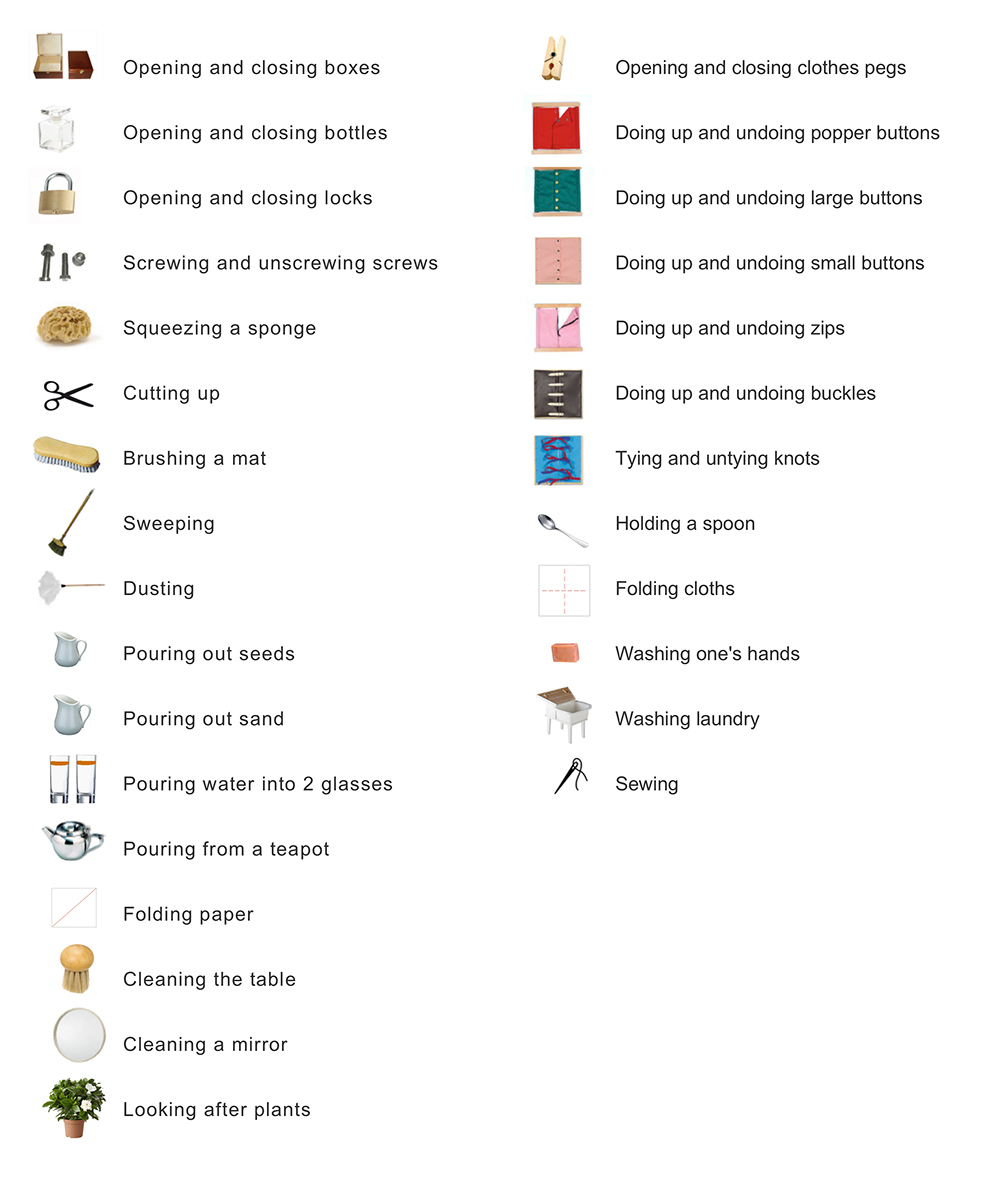

In parallel, we demonstrated practical daily activities to the children. You can view the video of how we presented all these activities here.

We advise you to present all of these activities before the children reach the age of 4½. They can be presented as soon as the children begin their first year and ideally through to the middle of the second year. However, the older children will be much less interested than the little ones in activities involving opening and closing clothes pegs, sweeping, buttoning and unbuttoning clothes, etc. The practical activities listed above are no longer challenging enough for most of the children aged over 5. For the older children it would be very fruitful to offer other activities which present a more interesting challenge such as weaving, knitting, looking after a vegetable garden, building huts or making small pieces of wooden furniture, preparing a meal (a fruit or vegetable salad, for example) or making small items of clothing, etc.

Why such everyday activities?

When looking at brain plasticity, we saw that children's neurons connect up and create specialised networks based on recurrent experiences. And so simply by being in our presence, they effortlessly incorporate our habits into the circuits of their brain. They then spontaneously express outwardly what has been previously encoded inside: one fine morning, we laugh when we see our child acting like us and wanting to sweep like us, talk like us, move like us and react like us: they reproduce the habits they have seen in their environment and which have directly structured their brain. And in replaying them, they strengthen the already existing neuron circuits and continue to become more specialised in their environment. This is how human beings construct the long chain of human history. Human beings are thus fundamentally adaptive creatures who, from a very young age, display great satisfaction and joy in reproducing what they observe in their immediate environment.

And the surprising thing - might nature be well-designed? - is that when the young child reproduces the daily actions through which their brain has structured itself, when they eat on their own, clean their own plate, put on their shoes on themselves, cut up fruit and help their little brother to get dressed, they are setting challenges for their rapidly developing executive functions: they have to focus their attention by inhibiting all distractions (inhibitory control), they have to retain in their memory the various stages and plan them (working memory), and they have to correct inappropriate movements and strategies (cognitive flexibility). The same applies when they try to button up their shirt, blow their nose, look after a plant, grate carrots, sweep the floor or simply put away their belongings. In other words, by affording them the possibility of being active in their daily environment, we enable young human beings not merely to pursue their cultural specialisation but also to construct the cornerstone skills of their intelligence, which are developing rapidly during this period.

Intelligence constructs itself, so let's take it seriously.

We have to be careful. We can't expect reality substitutes - such as plastic tea sets - to help our children develop their executive intelligence. We need to provide our children with real situations to imitate. Firstly, because they are interested in the objects which we use (environmental specialisation); and secondly, because fake objects do not allow children to exercise their executive skills – they offer neither a genuine goal, nor the possibility of correcting errors. Without a genuine goal, children don't need to plan the steps or retain them in their memory in order to achieve an objective (working memory) and, as a result, they don't need to adjust the steps and strategies (cognitive flexibility). A plastic plate handled roughly does not break and so offers no immediate feedback – it does not give the child the chance to adjust their movements or to channel their attention (inhibitory control). Plastic tea sets, plastic food, fake objects, fake kitchens, fake musical instruments and other substitutes for our reality will soon get broken, lost or forgotten. Our children will quickly grow tired of them and will need others which are more colourful and more this and more that, creating a vicious circle: whatever it is, it will never be quite enough. And there's nothing surprising in this, because their intelligence is unable to exercise itself with objects of this kind: they simulate reality without ever being as interesting as a real object used by an adult, thus frustrating their rapidly developing intelligence.

We should give them real objects, get them to chop real vegetables and fruit to prepare a meal, allow them to look after younger children (you'll notice that they'll have less need of dolls), show them how to lay the table, etc. We need to give them access to the daily reality of their culture. Proud of achieving independence with dignity, and supported by solidly anchored executive capacities, the children rapidly develop self-confidence, self-discipline, autonomy and perseverance. We need to refocus on the essentials – our children need to share in our lives rather than turning to toys.

Demonstrating these movements and activities in such a way as to engage executive skills to the maximum.

First of all, everybody has to wait their turn.

When the adult shows the movements and gestures to the child, the child must wait until the end of demonstration before reproducing them. They therefore need to inhibit their desire to act until the end of the demonstration while retaining in their memory the succession of steps to be taken and the goal to be achieved. The process therefore engages in an extremely effective way their inhibitory control and working memory.

Next, the goal needs to be explicit.

The adult states the goal clearly to the child. 'I'm going to show you how to hold a spoon properly'. This is a key point. Without an objective, they don't need to retain information, plan steps or remain flexible in their strategies, because without a defined goal it doesn't matter what they do.

The demonstration needs to be precise

The precision of the demonstration affords the child great pleasure because it challenges their rapidly developing executive functions. To do things properly, they will have to memorise better the order and the exact nature of the movements, control their movements more and also revise their strategies more in order to achieve the precision which they have been shown. As we have already emphasised, this level of precision and control engenders great concentration and a joyful satisfaction in a child of 3.

The demonstration needs to be done in silence

To ensure optimal transmission of the movements, we encourage you to perform the demonstration in silence. It would seem that speaking during a demonstration interferes with the child's ability to absorb the movements. If we want to provide children with items of vocabulary, we can do it before or after the demonstration.

They can detect their errors on their own.

When we tell a child that we are going to show them how to walk around the classroom, we draw their attention to the fact that we are avoiding the mats. And if they walk on a mat, that gives them immediate feedback: they need to control their movements more. The same goes for other demonstrations: if the mat won't stand upright, it means it hasn't been rolled up properly; if putting away a chair makes a lot of noise, it means that their movements were too abrupt, etc.

'I'm going show you how to roll up a mat. (...) Look – if it's properly rolled up, it stands up straight!'

'I'm going to show you how to walk around the classroom (...) Did you see? I'm avoiding the mats.'

'I'm going to show you how to put away a chair (...) Did you hear? I didn't make any noise.'

'I'm going to show you how to open and close a lock (...) Did you hear the 'click'? That means it's closed properly!'

The child can then perfect the action on their own, repeating it as often as they wish without requiring feedback from the adult, because they can spot their errors themselves. In Gennevilliers some children rolled up their mat a dozen times in a row until it would stand perfectly upright. At this point, the adult's only task is not to interrupt and to ensure that the child can go about this formative repetition unhindered.

The demonstration needs to be individual.

Why? Because at the age of 3, their inhibitory control and working memory are weak. If the demonstration is done with 2 or 3 classmates, the child will forget the movements demonstrated by the adult in the time it takes the others to each perform the movements in turn; moreover, they would not have the patience to wait while 2 or 3 other classmates were performing the action. An individual demonstration does contain its own interesting challenge, but this is not a cause for discouragement: the child can memorise what they are being shown and learn to control themselves for the duration of the demonstration. Lastly, an individual demonstration allows you to offer the child the appropriate assistance so that they can make progress without you ever performing the action for them.

In addition, an individual approach allows you to rapidly identify the children who have difficulty controlling themselves, memorising things over short periods or modifying their strategy when it isn't working. With these children, you need to be more patient and trusting and to encourage them more than the others, getting them to repeat this type of exercise every day so that they can practise, develop and progressively master these executive skills. And the game is worth the candle because, as you'll see, one fine day these children will undergo a transformation.

Formulated objective & principal objective

When one of these activities is shown to the child, the objective to be achieved is always formulated: 'I'm going to show you how to clean a table', 'I'm going to show you how to use a screwdriver', 'I'm going to show you how to fold paper”, etc. But we should be under no illusions. Initially, the principal objective of these activities is not that the child cleans, folds or uses a screwdriver perfectly, but rather that the child develops their executive skills by trying to clean, fold or use a screwdriver perfectly. The essential element is everything that the child constructs within their brain in attempting to achieve the goal we have formulated for them. We therefore urge you not to interrupt the child who, for the third time in a row, is cleaning a table which is already perfectly clean, or buttoning up and unbuttoning the same button for the tenth time, because they are motivated not by the end result but entirely by the process itself, which is exercising their rapidly developing executive intelligence.

This should change our whole approach: the expectation of the adult should not be that the child immediately achieves the formulated objective, but rather that they can satisfy their need to exercise their executive skills as these skills develop.

For these activities to make sense culturally, it is also important to adapt them to the culture of the country. For instance, one idea for the North African teachers who are following our work would be to propose tea service trays or another typical activity.