All you need is love

We have seen how the experiences of a child during the first two years of their life influence their future cognitive development. This postnatal period is of fundamental importance. Babies absorb everything in the environment into which they have just been born. We have seen that the newly born child is an attentive observer who studies and explores the world in great earnestness. Such exploration is foundational, since their experiences are directly structuring their brain. In other words, we parents and educators have a 'great responsibility': how can we be sure of providing a child with the appropriate experiences? What do they need in order to construct themselves during this critical period?

Very young children do of course explore the world and are nourished by their active experiences – this is a fundamental need. But if they can do so while being sympathetically supported and guided by our attentive presence, it is even better. This seems to be the most important element during this period of intense development. Experience life, but experience it with us. Interacting with children through our gaze, our voice and our body genuinely drives their development, and so it is enough for us to be in their presence, to observe and to be a party to their little achievements. For example, we can walk like they do, taking the time to stop when they do and marvelling with them at each new discovery; or we can support their spontaneous initiatives, when for instance they try to feed themselves although they haven't quite mastered their arm movements. Ultimately, it doesn't really matter what we share with them - it can be a smile, tears, a bath, a story or a song. We merely need to support them in their exploration of the world by being present in the relationship.

This attentive presence is of fundamental importance. Human beings are eminently social creatures and their brains need the love of others in order to develop correctly – our gaze gives them the feeling that they exist and our cuddles the feeling that they are loved. The brains of these social embryos can then mature and develop their full potential.

We already know at a more or less intuitive level that our presence at a child's side is central to their development; but what we are no doubt less aware of is the decisive impact of our attentive presence during the critical period of the first two years of life. Two studies highlight the dramatic consequences of a lack of an attentive presence during these first two years.

In the early 1990s in Philadelphia, Dr. Hallam Hurt and her team studied the damage caused to the children of mothers who were addicted to cocaine. Over several years they monitored two groups of newborns from the same disadvantaged socio-economic background: one consisted of newborns whose mothers were addicted to cocaine and who had thus been exposed to this drug during pregnancy (the test group), while the other (the control group) consisted of newborns who had not been exposed to the drug. At the age of four, and much to the surprise of the researchers, no significant cognitive differences were found between the two groups. Exposure to cocaine had not impacted (or only very subtly) on the children's development. On the other hand, in both groups (test and control) the children's IQ was much lower than the average for their age group.

This unexpected result prompted the researchers to take an interest in the factor which was common to all these children: a disadvantaged social background marked by violence. Could this environment have disrupted cognitive development more than exposure to cocaine in utero? The answer was yes. The analysis of the data showed that environmental factors such as exposure to violence and a lack of human interaction were more detrimental to cognitive development than prenatal exposure to the drug. This goes to show just how fundamental human interactions are in constructing human intelligence: while embryos may be able to cope with exposure to cocaine while their cells are being formed, newborns by contrast are much less able to cope with an absence of support while their brain is developing. Violence and a paucity of human interactions correlate directly with a lower IQ and a reduction in the size of the hippocampus (an organ linked to memory), and thus to poorer performance in tasks involving memory.

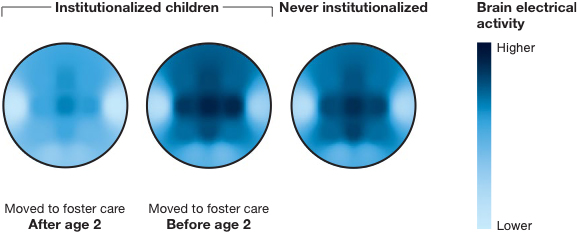

Another famous study, known as the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, brought to light an extreme case which showed that being fed and clothed is not sufficient for human development. The study was carried out after the fall of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, when the atrocious conditions in state orphanages came to light. Babies were left on their own for hours at a time in beds with bars; there were several of them to a bed and sometimes they were entirely deprived of daylight. They had minimum contact with the adults: one carer was responsible for feeding 20 children and tending to their hygiene but she had no further interactions with them. These children were therefore deprived almost completely of adult contact and, as a result, their social and emotional behaviours were highly perturbed. Moreover, their brain volume was below average, as was the level of electrical activity in their brains. Being so dramatically deprived of interactions had thus resulted in the under-development of the brain and in greatly reduced brain activity. The children were eventually all placed in foster homes and in 2001 researchers compared the development of children who were placed in a foster home before the age of 2 with the development of the children from the orphanage who had been placed in a foster home after the age of 2.

The results unambiguously revealed that the children placed in a foster home before the age of 2 showed little or no cognitive or social differences in comparison to children of the same age: by the age of 8, the electrical activity in their brains was normal. Benefiting from a rich and nurturing environment before the end of that period of great plasticity – the first two years of life – had proved to be decisive and was a source of resilience. In contrast, the children placed in a foster home after the age of 2 were still suffering from abnormal development. Exactly the same was true of the Philadelphia children: the children who had been in an institution but who moved to a foster home before the age of 2 had normal brain activity by the age of 8, whereas (as can be seen in the visual below) the brain activity of children who moved to a foster home after the age of 2 remained much weaker.

These two studies are telling us something important: although we possess innate and sophisticated prewiring for learning, we are first and foremost social creatures, and if we are deprived of social support during the years when the brain is maturing, our innate predispositions can run aground on environmental factors. Although we are programmed to learn, we will nevertheless be left with cognitive deficiencies if our essence as a social being is not respected.

The emphasis currently placed on the importance of social relationships in learning is not a precept invented by so-called alternative education, as these two studies demonstrate. Social bonding is the cornerstone in constructing our intelligence: it is one of the laws of life which we now have to acquaint ourselves with and respect.

Compilation consisting mainly of videos sent by parents who are following us.

Photographs by Lynn Johnson.